In my experience, the challenges that growing companies struggle with rarely stem from a lack of good ideas. Good ideas are everywhere.

But it takes more than good ideas to build and grow a business. It takes people to bring them into reality. Are those people collaborating and sharing their expertise, or are they in conflict and keeping it to themselves?

Do they have the resources necessary to execute on their ideas? Or are they constantly under pressure to pluck only the lowest-hanging fruit through bare minimum means, while putting their greatest ambitions on the back-burner?

These are the circumstances that suffocate creativity and destroy value in an organization. That’s why I knew that if I was going to start a company, our first product would have to be the company itself.

Companies themselves are a kind of product, distinct from the products they create. They are systems that process inputs (such as creative work and technology) into more valuable outputs — the products and services that are ultimately sold. The ability to effectively transform those inputs into outputs essentially defines the potential of a company.

Companies themselves are a kind of product, distinct from the products they create.

You would expect that, with the absolutely critical use case the company-as-a-product serves, it would be designed and optimized with the same care as the products it creates. But this is rarely the case. Instead, it’s largely left to chance, or channelled into a misguided focus on “culture” that is more about theatrics than it is about creating tangible benefits for companies and their employees — not to mention their customers.

That doesn’t mean culture isn’t critical. But you can’t just conjure it up or enforce like a set of commandments; it’s the result of what you do.

Culture is the programming of an organization, the energy that motivates every component into action, the perspective it projects into the world. And yet so often there seems to be ongoing tension between a company’s culture and the business it does daily.

To set up Narative’s culture to thrive free of that tension, I first looked at how its business model could support it.

Building a business

Before deciding to start up Narative, I’d worked as a product designer at both creative agencies and startups for over a decade.

I’d recently left a full-time role and was excited to start a company where I could build the kinds of products I’d always wanted to, with a team I would play an active role in building.

Doing that would require the financial resources to attract and retain top talent in a competitive marketplace. However, I also wanted to avoid raising capital and giving up equity at this stage; I felt it was important to keep control over the quality of our products and to focus on building value for the team, rather than for investors.

This ultimately leads to the decision to split Narative’s focus between building digital products and strategies for client-companies looking to hire an outside team (which we call Narative Studio), while simultaneously developing our own products in-house with the goal of bringing them to market ourselves (which we call Narative Labs).

The benefits of this split are equal parts financial and cultural:

Diversifying our revenue beyond our own products would give us stability and flexibility to pursue projects that we believe in, and grow the team more quickly.

Alternating between client work and internal projects would continuously expose us to new strategies, challenges and solutions, strengthening the quality of our output on all fronts.

Despite the upsides, there are clear risks to this approach. Client work and product development are both resource-intensive individually, and we wouldn’t have much talent to spare.

With client work being our initial source of revenue, any required shift in resources would be away from building our own products. This meant our major vulnerability would be finding time to develop and bring to market our very first product.

It also raised the question of whether building those products was simply a distraction from generating leads and reliable revenue with client work.

But the goal of founding Narative was never just to spin up another creative agency (which is why we never refer to ourselves as one). It was to create a company where good ideas could be pursued no matter their form, by a team with the talent and the means to pursue them.

And so rather than over-fixate on the risks, we instead looked to our first product as an opportunity to fund that pursuit.

The goal was to create a company where good ideas could be pursued no matter their form, by a team with the talent and the means to pursue them.

If we could launch a viable SaaS (Software-as-a-Service) product, and acquire just a few hundred users at an industry-tested price point, it would generate enough revenue to cancel out our primary expense: salaries. This could expand our runway by more than 50%, providing financial security for the company and the resources our team needs to succeed.

Like any good business story, we've started working on an idea even before Narative existed. Something we did in our free time, to solve a workflow problem for ourselves.

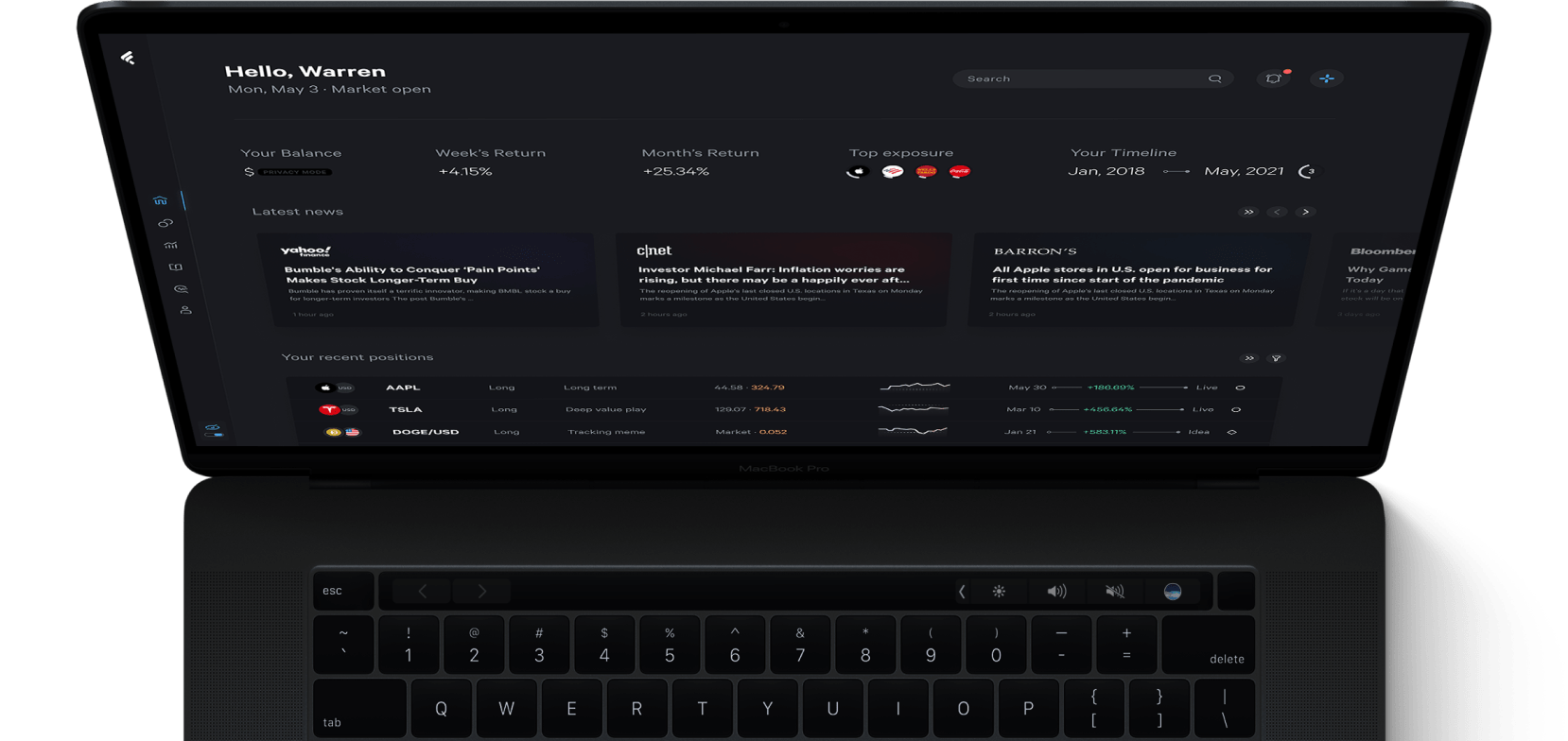

That idea is now called Fey, a platform for strategic, focused trading for self-directed investors. Fey is designed to eliminate the many issues, minor and major, that plague investor workflows every day.

Fey is the ultimate investing experience built from the ground up, meticulously designed for the self-directed investor.

After building Fey's first landing page, hundreds of users registered to get access to the product, and competitive analysis revealed many opportunities to solve real pains in the market, rather than only for ourselves. It would be premature to call this product-market fit, but the signs were good that it could be achieved.

It just needed the right team to make Fey something even more serious.

Building a team

Rather than focusing solely on design and development experience, academic degrees or those with agency backgrounds, we prioritized bringing on individuals with real-world experience in startups and scaling companies — both for the sake of Narative’s growth as a startup, and to provide our clients with the skills and guidance they need.

While the volume of experience wasn’t critical, it was important to collect informed perspectives on the challenges growing companies can face. Many agencies can do branding, design and development (we included). Not as many can integrate that work into the metrics growing companies are focused on, like user acquisition, churn and revenue, to name a few. It would also bring valuable awareness of the cultural pains that can come with that growth.

As a designer co-founding a business, I knew there were gaps in my knowledge and perspectives I would need others to support. And as early conversations with potential team members began, I felt that the most promising candidates also spoke frequently of their own weaknesses and vulnerabilities, and how they hoped to grow and overcome them.

As a designer co-founding a business, I knew there were gaps in my knowledge and perspectives I would need others to support.

To build a company that could continuously adapt and grow, it was important to center the team around a growth mindset — the idea that our talents and skills can be developed through thought, effort and feedback, as opposed to being fixed and innate elements of our personality.

That might sound obvious, but in reality, businesses don’t always encourage internal growth by design. Carol Dweck, a professor of psychology at Stanford University, wrote about this for Harvard Business Review:

“When we face challenges, receive criticism, or fare poorly compared with others, we can easily fall into insecurity or defensiveness, a response that inhibits growth. Our work environments, too, can be full of fixed-mindset triggers. A company that plays the talent game makes it harder for people to practice growth-mindset thinking and behavior, such as sharing information, collaborating, innovating, seeking feedback, or admitting errors. To remain in a growth zone, we must identify and work with these triggers.”

The more open you are in any relationship, personal or professional, the more vulnerabilities you’ll inevitably expose. If a professional environment only rewards success and punishes the mistakes or weaknesses that are the natural stepping stones to growth, the entire organization can revert to a fixed mindset and become frozen in place.

In 2012, Google began an internal research project to identify the common traits of high-performing teams. They discovered that the defining factors had nothing to do with talent nor individual personality traits; instead, the key was in how comfortable the group as a whole felt being authentic and vulnerable with each other. Psychologists and researchers define this as psychological safety, the “shared belief held by members of a team that the team is safe for interpersonal risk-taking.” Building a growth mindset starts with creating an environment where people feel safe simply being themselves.

Ensuring open communication from the outset was critical for another reason: Narative would launch as a 100% remote company. Like our decision to pursue both client work and our own products, the motivation behind this was equal parts financial and cultural: not having an office keeps our fixed costs down, and it simply seems like bad business to limit your talent search to within an hour of yourself.

Many employers bristle at the thought of requiring — or merely allowing — their teams to work remotely, but this is largely an issue of trust. “How do I know if people are really working if I can’t see them doing it?”

Measuring a team’s output based on the perceived time and effort invested is a destructive attitude, to begin with, distracting them from focusing on doing work that truly makes a difference.

Much of the time spent under the guise of hard work is really spent posturing, politicking and otherwise keeping up the appearance of selfless effort. The rigid hierarchies of many workplaces big and small demand it, treating opportunities for professional growth and success as a zero-sum game.

It obviously doesn’t need to be this way, and it’s one of the reasons we’re keeping Narative’s hierarchy as flat as possible.

We promise everyone who joins the team the opportunity to make “executive-level decisions.” We aren’t looking for people to merely execute the ideas we already have in place. Instead, every member of the team plays an active role in deciding what products we build, which clients we pursue and how we approach every problem.

We incentivize contribution and motivation not with an ever-escalating ladder of titles and tensely-negotiated raises, but through providing an opportunity to create the kind of company each of us have always wanted to work at, and to bring our ideas to life — along with helping others do the same.

Building the future

While we’re excited about the products we’re building in-house, we don’t see our work with clients as merely a means to an end. As I wrote earlier, we want to pursue good ideas, no matter their form. We’re equally excited about working with innovative businesses to help build their story and bring it to the world.

One of those innovators is Hopper, who we’ve been happy to have as one of our early clients. We documented the process of building Hopper.com to better communicate what’s unique about their product, people and brand.

The positive reception to that project has been extremely gratifying, along with seeing how our relationship with the Hopper team has grown over the time we spent working on it. Today, they consider us partners and seamlessly integrate our work into theirs in ways even we couldn’t have imagined.

Our work with Hopper has also helped us shape our approach to clients in general, as we focus on longer-term, high-value engagements with minimal overlap between clients. This allows us to stay focused on each client while still freeing up the resources necessary to move forward with ideas of our own.

Our company isn’t about creating a particular thing; it’s about creating the context to make things great.

Meanwhile, the assets and methodologies we develop for our in-house products end up finding their way into our work for clients like Hopper. The work we do for our own products improves the quality of the work we can provide for our clients, and vice-versa. The creation of each output strengthens every other output.

This doesn’t happen by chance; it’s explicitly part of the way we’ve designed our company to function, as a product in and of itself.

And importantly, this cycle of growth can exist regardless of what products we’re building or which clients we’re working with, because our business isn’t about a singular “good idea”.

If a market we want to enter changes, or we simply reassess our plans and want to pursue something else, our company won’t face an existential crisis because it isn’t about creating a particular thing; it’s about creating the context to make things great.

In less than six months, we’ve exceeded our 7-figure revenue goal and invested it directly back into the team, now six people strong and sure to grow more soon. We’ve shipped some amazing client projects, and are hard at work behind the scenes bringing two of our own products to market — one being Fey, and another we’ll talk more about soon. And we’ve done it all with zero funding or loans.

We’re excited to move forward with trust at the center of everything that we do, to meet like-minded companies with big ideas we can help bring to life, and to share more of that journey here with you.